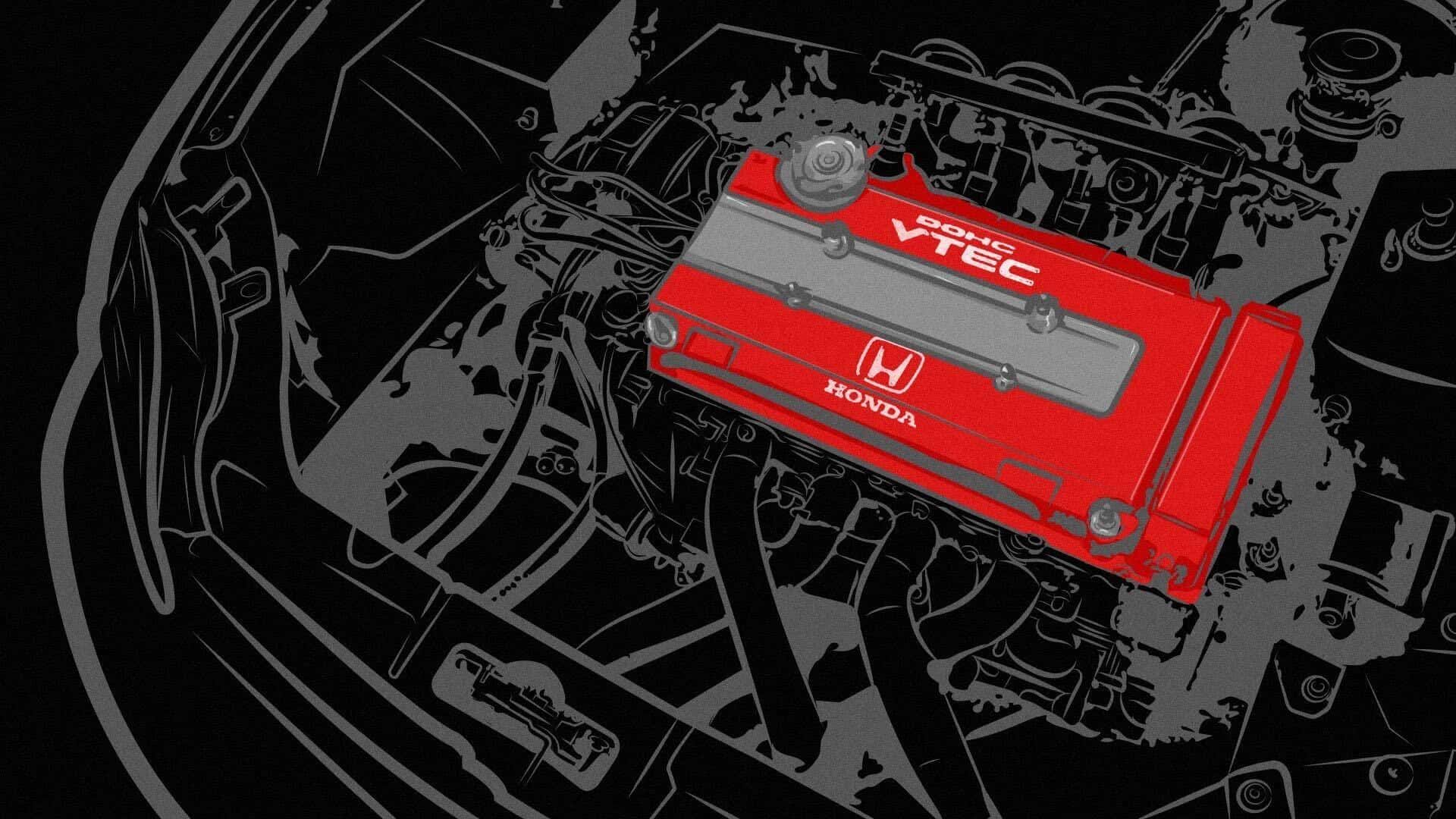

HOW VTEC WORKS: AN EXPLAINER

A closer look at one of the most iconic names in engineering.

There are few sounds in the automotive orchestra as distinct as the VTEC kick. Characterized by a sudden jump in tone (and volume) coming from a high-revving, naturally aspirated Honda engine, the VTEC whomp has scored some of the greatest sports cars of all time. And also the neighbor kid’s straight-piped Integra. (Sorry—that was probably me).

It’s one of the longest-lived—and most oft-meme’d—pieces of automotive technology. With naturally aspirated motors receiving a stay of execution, it’s time to take a look at what, exactly, keeps us so hooked on them. There’s no better place to start than VTEC.

Honda And The Naturally Aspirated Motor

Honda has long sought ways to improve the technology found in naturally aspirated engines. Its first runaway success in America came with the introduction of Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion (CVCC). Honda introduced CVCC with the Civic in 1974, at the height of the OPEC fuel crisis. The system used a pre-chamber in the head, allowing for more complete fuel burn. The pre-chamber’s auxiliary valve sent a richer air-fuel mixture nearer to the spark plug, while the standard inlet valve sent a leaner mixture throughout the rest of the combustion chamber.

Compounding Reward

The beauty of VTEC is that it is so mechanically straightforward that it can be combined with other engine technologies for more control over an engine’s behavior. Honda has used this to create i-VTEC, which pairs variable valve timing with VTEC, allowing for further optimization of airflow. In 2006, Honda developed a motor that allowed for infinitely variable cam phasing while also incorporating VTEC. The company intended to put it into production by 2010, but shelved the concept.

Instead, last decade, Honda moved towards turbocharging as emissions regulations—and expected power outputs—continued to toughen. In Honda’s turbo VTEC motors, the extra lobes are found solely on the exhaust camshaft, as the turbo is fed by exhaust airflow. The more aggressive lobe engages under certain conditions where turbo lag is likely—such as partial throttle or low RPM acceleration—to help the turbo spool more rapidly.

Unfortunately, exhaust-only VTEC doesn’t have the characteristic bwwaaa–WAAAA sound—that comes from the intake. Still, Honda has used it well to its advantage, with the Civic Type R achieving rave reviews for its throttle response and lack of turbo lag. Whether naturally aspirated motors are here to stay for good is anyone’s guess, but it’s clear by now that as long as there are Honda engines, there will be VTEC.

How Things Work

2024-07-01T14:29:50Z dg43tfdfdgfd